Green US Army and Allies

|

|

Blue: US Navy and US Marine Corps

|

|

Milestones of the Pacific war, Island hopping |

|

| back to homepage "English" |

|

Milestones of the Pacific war |

|

Strategy and execution, "island hopping" |

| by Wilfried Eck |

|

|

|

Green US Army and Allies |

|

Blue: US Navy and US Marine Corps

|

|

|

|

Island hopping - often quoted, rarely understood.

The terms "island hopping" and "leapfrogging" did not become known to the public

until after the end of the war. In a newspaper interview, General Douglas MacArthur, former commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army in the Southwest Pacific

area, said. According to this, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (Commander in Chief of

the US Navy) had caused high losses with a wrong strategy, while his "leap

frogging" and cutting off the Japanese supply by skipping individual islands,

had avoided losses. His "island hopping" had been the winning strategy.

What Douglas MacArthur failed to mention in this statement was that, with the exception of the Philippines, islands north of the equator were not part of his area of operations and that "leap frogging," moving in sequence from one coastal position to the next, was a derogatory term used by the U.S. Navy to describe his actions in Papua New Guinea. But the media had its headline, and for lack of better knowledge - Admiral Nimitz never commented on it - island hopping and cutting off enemy supplies became the basis of all further reports.

In the spring of 1942, with the battles for Midway and

Guadalcanal still in the future, the Combined Chiefs of Staff were faced with

the question of how and by whom the war in the Pacific should be fought. At

issue were the competing strategies of General Douglas MacArthur (US Army) and

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz (US Navy). MacArthur wanted to advance through Papua

New Guinea to the Philippines and then join the Navy in pushing north to Japan.

Nimitz, on the other hand, planned to reach the Philippines across the central

Pacific with the Navy and attached Marines and, further on, together with the

U.S. Army. Since there was agreement anyway on the last leg, it was decided on

March 30, 1942, to divide the East Asian war zone into three zones (the British the part of the Indian Ocean not relevant

here and Burma) and to let the plans of MacArthur and Nimitz run in parallel.

The dividing line (with the exception of the Philippines) was the equator west

of 129 degrees longitude. Support in individual cases was of course not excluded.

This was especially true for the battles for the Solomons and the weakening of

the strongly fortified city of Rabaul with its large harbor and five airfields.

This resulted in two completely different war zones, which were increasingly far

apart. On New Guinea, conventional land warfare, but complicated by the jungle.

Since modern warfare requires a steady supply of fuel, ammunition and rations,

cutting off enemy supplies was central to General MacArthur's strategy. - As for

supplies, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz had the problem of vast distances. Already

the easternmost part of the Japanese dominion was 3,900 km (2106 nm) away from

Pearl Harbor, every approach thus a logistical challenge, supply bases

indispensable. On the offensive, superior Japanese naval airpower was a problem.

Japanese naval aircraft had tremendous range, most notably the A6M2 "Zero Sen"

fighter, which could not only out-curve any opponent, but had a flight time of

over 10 hours on lean mixture settings.

As for the alleged strategy of island jumping, cutting off supply by jumping

over an island, this claim leads itself ad absurdum. If you jump over an island

held by the enemy, you are stuck on the newly acquired island just as the enemy

is stuck on the island you jumped over. You can't sink ships with foot troops.

But you can, see battle of Midway, with airplanes. If you have an airfield, you can keep

the entire area free of enemy shipping. Your own territory is determined by the

range of your aircraft. If this is large enough, you control an entire territory,

not just a single island. Conversely, it was imperative for the U.S. Navy to

weaken the Japanese air force - to which the same applied - to such an extent

that it could no longer endanger its own actions. Incidentally, the role of the

submarines must not be ignored.

On the offensive, Admiral Nimitz planned expansively. It would have been foolish to try to jump from one island to another, because the enemy would have quickly adjusted to the order and taken countermeasures. For that matter, it would have taken far too long to individually capture a multitude of islands scattered throughout the vast Pacific to get to the Philippines on order. The Allies had experienced how time-consuming, material-intensive and manpower-intensive it was to take a chain of islands one after the other in the Solomon Islands (see overview) - there was no other way at that time because aircraft carriers were scarce and the range of American aircraft was shorter than that of Japanese aircraft.

For Nimitz and the U.S. Navy, islands were only of interest if they were either strategically located or had an airfield from which Japanese aircraft could threaten their own operations or if they were later thought to be used themselves. Nimitz's offensive weapons were aircraft, especially those of the aircraft carriers. Since Japanese aircraft carriers no longer played a role after Midway, they could be used to attack any point in the Pacific and decimate facilities and the enemy's aircraft inventory. Which was then done extensively, at widely separated locations, seemingly incoherently, so that Japan could see no method. Equally important was to prepare and support the landing of own troops. Accordingly, airfields and anchorages for the fleet were needed, ideally both together. Atolls, more or less circular island chains of 30 - 50 km (16 - 27 nm) in diameter, were best suited for this purpose. Blocking the only access gave a safe harbor, suitable islands accommodated storage and other spaces. This and repair or new construction of an airfield was done by the "Sea Bees" (from CB, Construction Battalion). Securing to the outside and possibly "cleaning up the area" was then the job of Marine Corps aircraft units. To prepare the next venture, long-range bombers of the U.S. Army Air Force could also be stationed, if the capture was not in favor of the USAAF anyway, as in the case of the Marianas and Iwo Jima.

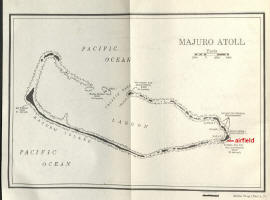

After the joint venture of the U.S. Army, Navy, Marine Corps and New Zealand, the recapture of the approximately 1.000 km (640 nm) long island chain of the Solomon Islands drew to a close in the fall of 1943, Admiral Nimitz was able to turn his attention to his own tasks. The first step, in October 1943, was the Gilbert Islands at the eastern end of Japanese-occupied territory, some 1.200 km (648 nm) from Guadalcanal. The main target was Tarawa Atoll with its main island of Betio, only 3,200 m x 720 m (3,500 x 788 yds) in size but with a well-developed airfield. To divert attention from the actual attack target, the Apamama/Abemama and Makin/Butaritari atolls were to be captured in parallel. For this purpose, a fleet of 17 aircraft carriers with about 850 aircraft, twelve battleships, eight heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, 66 destroyers, and 36 transport ships with two divisions of naval infantry was ready on Nov. 20. Tarawa and Makin fell after three days, Apamama, which had been attacked on Nov. 21, fell on Nov. 25, 1943. The next step was the northward Marshall Islands, here the urgently needed anchor and supply bases for the fleet were to be built. The Majuro atoll about 750 km (405 nm) north of Tarawa formed the beginning on 31.01.1944, taken without own losses in one day. The capture of Roi and Namur islands of Kwajalein Atoll, located 680 km (367 nm) northeast of Majuro, was more difficult and lasted from 31 Jan-07 Feb; Eniwetok with the main island of Engebi, 600 km (324 nm) farther west, followed Feb. 17-23, 1944. With U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Army Air Force aircraft stationed on these three atolls, a wide area could be covered. The remaining Japanese-held islands of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands thus posed no threat to the further westward advance and could be left to their own devices.

Since 20 October 1943, always part of the fleet: Escort Carriers (CVE). Partially converted from oil tankers and merchant ships they protected fuel, ammunition and supply convoys from submarine and air attacks, provided training carriers and more, but above all were always directly involved in supporting the land assault operations of the Marines. (in case of Tarawa with eight ships). Because of the high demand, their number later exceeded that of the fleet carriers. See page "Escort Carriers"

This means that - as far as Admiral Nimitz, the US Navy and the Marine Corps are concerned - the subject of island jumping is actually settled. The next targets were "big lumps" where there was nothing to jump over. First, the Marianas (to create bases for B-29 long-range bombers), about 1.800 km (970 nm) away, the Philippines etc. even further. Whether this can be called island hopping is left to the reader (m/f/d). As off Papua New Guinea, Japanese supplies - if relevant - were not suppressed by island hopping, but by submarines and sea surveillance by aircraft.

As for MacArthur's claims of high casualties, he cannot be disagreed with regarding Tarawa and Peleliu. In both cases, the losses were caused by bad planning. At Tarawa, the attack had been made at low water, which was the undoing of many landing craft because of the offshore reefs; incidentally, all Japanese gun and machine gun positions were excellently positioned, camouflaged and protected. On Peleliu, it was the positions bunkered in the Umurgrogol mountain range, which could hardly be seen from the outside, and the attack date itself. The Japanese naval air force no longer posed a threat to the invasion of the Philippines. In general, however, American losses were much lower, a ratio of 1:10 not uncommon.

"Island hopping" MacArthur style:

In the Quebec Conference of August 17-24, 1943, General MacArthur's "Elkton III" plan had been endorsed not to attack the heavily fortified Rabaul on New Britain, but to starve it out by cutting off supplies. Accordingly, MacArthur faced the unfamiliar task of occupying the Admiralty Islands, 320 km (173 nm) north of New Guinea, as part of his now renamed "Cartwheel" plan. They resemble a U turned to the left with the two main islands of Manus and Los Negros at the southern end and northern four islets in an arc to the west. "Seeadler Harbor" (the name from German colonial times still existed) provided an anchorage for the fleet, Los Negros and Manus each had an airfield from which to control the area as far as Rabaul. Twelve U.S. Navy destroyers brought Army and Australian troops ashore on an unguarded point on Los Negros on February 29, 1944, followed by others on March 15 on the much larger island of Manus, connected to Los Negros by a bridge. However, due to swampy terrain and dogged Japanese resistance, the occupation proved more difficult than expected. However, after the northern islets had also been occupied, the operation could be officially declared over on May 18, 1944, after the last pockets of resistance had been eliminated. The prevailing opinion had it that the operation saved more lives than it cost, since it also made the capture of Truk, Kavieng, Rabaul, and Hansa Bay unnecessary, thus accelerating the Allied advance to the Philippines by several months.

This action by General MacArthur corresponds exactly to his statement in the newspaper interview. He had taken the small Admiralty Islands, which were relatively close together, by "leap frogging", one after the other. He had not jumped over any of them, but by taking the airfields on Los Negros and Manus as well as "Seeadler Harbor", he had achieved his goal of cutting off Rabaul from supplies. U.S. Marine Corps airfields in the western vicinity of Rabaul completed the encirclement. However, its still strong garrison - mainly due to a lack of aircraft - was no longer of any importance in the course of 1944, as was the Truk supply base (1,800 km northeast of New Guinea), which had also become insignificant due to the onward movement of the war front. Whether both received supplies or not was of no military significance.

Cutting off enemy islands from supplies by skipping them was neither necessary nor practiced by the U.S. Navy. Japan had less and less to counter the increasingly large U.S. aircraft carrier battle groups. Its ground forces, scattered on countless islands, could not support each other and fell victim to the material and manpower superiority of Allied forces if not simply left to their own devices because they were irrelevant to the advance.

However General Douglas

MacArthur may have come to his conclusions, he had hit bull's eye with his

interview. "Victory by island hopping" made a snappy headline that the common

man in the street immediately understood and could easily pass on. How it had

gone in reality, nobody wanted to know so exactly. And so it has remained to this day.

| "Island hopping" really meant: only capture strategically important islands |

|

|

|

|

|