|

|

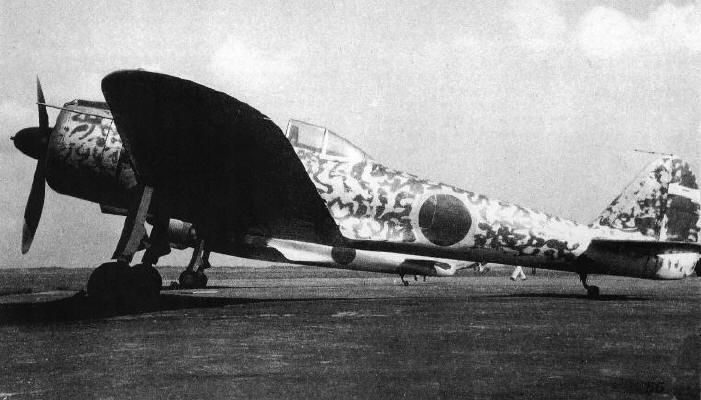

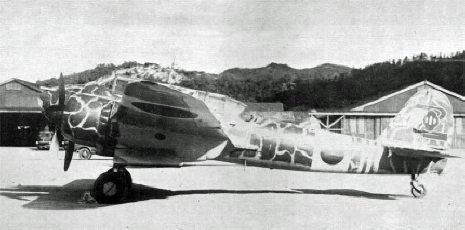

The photo on the

left shows the A6M3 Zero flown by top pilot

Hiroyoshi Nishizawa of the "Tainan" Air Group on Rabaul. The unit insignia "V"

has been retouched away by the censor. If you look closely at the photo, you

will notice that bright spots are only just behind the cowling and they become

less and less towards the back. Another striking feature is the (almost)

straight dividing line from light to dark at the lower edge of the cockpit

glazing, whereby the struts are light throughout. A technical reason why the

paint on the cockpit struts is completely chipped, behind the cooling flaps

almost completely, but behind the national insignia almost not at all, has

not yet become clear to me.

In reality, the paint has not chipped off

at all in the light spots. On the bright spots you can still see the

original light gray color in which the machine was originally delivered.

Since they were forced to operate from land after June 4, 1942, and

appropriate camouflage seemed necessary, the dark green camouflage paint had

to be applied by hand afterwards. This did not have to be even, an irregular

pattern enhanced the camouflage. - But this was only during the transition

period to the later general standard, factory-applied dark green over

greenish gray. As before, always over a primer coat. Later on, small

abrasion marks could be seen in particularly stressed areas, but never

flaked paint. Because the

manufacturers worked equally for army and navy, there were no differences in

the quality of colors.

Color drawings (profiles) showing Japanese Navy

aircraft with large blank areas are far away from of reality. |